Shakespeare’s Sonnet 1 Analysis: Meaning, Themes, and Line-by-Line Breakdown

When you open the massive collection of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets, you aren’t immediately greeted with the romantic cheese of "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" Instead, you find an argument. A demand, actually.

Sonnet 1 is the opening act of the famous "Fair Youth" sequence. In these first 17 poems, known as the Procreation Sonnets, the Speaker isn’t trying to seduce the young man; he is trying to convince him to have children.

Why? Because beauty is a loan from nature, not a gift.

In this Shakespeare’s Sonnet 1 Analysis, we will break down exactly how the Bard uses economic metaphors, paradoxes, and floral imagery to accuse a beautiful young man of being stingy with his genetics.

The Text: Sonnet 1

Before we dissect the meaning, it is vital to read the poem aloud to hear the rhythm.

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory;

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

Line-by-Line Analysis

Shakespeare structures his argument like a lawyer in a courtroom. He moves from a general rule of nature to a specific accusation against the Youth.

Quatrain 1: The Biological Imperative (Lines 1–4)

The poem opens with a universal truth: "From fairest creatures we desire increase."

The meaning here is straightforward. When we see something beautiful (the "fairest creatures"), we want more of it. We want it to "increase" (reproduce). Shakespeare uses the metaphor of "beauty's rose" to symbolize ideal perfection.

However, roses wilt. The Speaker acknowledges that the "riper" (the older parent) will eventually die. The only way to cheat death is to leave behind a "tender heir" who will carry the memory of that beauty forward. This sets the stakes: Immortality is possible, but only through children.

Quatrain 2: Narcissism and Self-Consumption (Lines 5–8)

Here, the tone shifts from philosophical to accusatory.

The Speaker turns to the Youth: "But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes..." The word "contracted" does double duty here. It suggests a legal contract (betrothed to himself) and a physical shrinking (limiting his world to his own reflection).

Shakespeare then uses a powerful image of self-consumption: "Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel." Imagine a candle feeding on its own wax until it burns out. By loving only himself, the Youth is wasting his energy. This leads to the central paradox of the poem: "Making a famine where abundance lies." The Youth has an abundance of beauty, yet by hoarding it, he creates a starvation of beauty in the world.

Quatrain 3: The Enemy of Time (Lines 9–12)

The Speaker appeals to the Youth's vanity. He calls him the "world’s fresh ornament" and the "only herald to the gaudy spring." He is the top celebrity, the trendsetter, the sign that spring has arrived.

But there is a trap. By refusing to reproduce, the Youth is "burying his content" within his own bud. Think of a flower that refuses to bloom and spread seeds; it rots inside the bud.

Shakespeare creates a brilliant oxymoron with the phrase "tender churl."

- Tender: Young, soft, beautiful.

- Churl: A stingy, rude, low-class person (a miser). The Youth is physically soft, but emotionally hard and greedy.

The Couplet: The Final Warning (Lines 13–14)

Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

The final two lines deliver the verdict. The Youth has a duty to the world. If he doesn't have a child, he is a "glutton." This is ironic because usually, gluttons eat too much food. Here, the Youth is a glutton because he is consuming his own beauty rather than sharing it.

If he dies childless, he and the grave will "eat" the beauty that rightfully belonged to the world.

Major Themes in Sonnet 1

Any robust Shakespeare’s Sonnet 1 Analysis must look beyond the plot and examine the underlying themes that drive the sequence.

1. Beauty as Currency

Shakespeare doesn't view beauty as a static trait; he views it as an economic resource. He uses words like increase, contract, abundance, waste, and due. The argument is capitalistic: You have been given a loan of high value (beauty), and you are expected to pay interest (children). Hoarding it is fiscally irresponsible.

2. The Battle Against Time

Time is the villain in almost all of Shakespeare's sonnets. In Sonnet 1, Time is the inevitable force that will make the "riper" decease. The only weapon humans have against Time is biological reproduction. Art can preserve a name, but only a child can preserve the face.

3. Selfishness vs. Duty

We often think of having children as a personal choice. Shakespeare frames it as a moral obligation. To him, refusing to pass on your genes when you are "fair" is an act of cruelty toward humanity.

Literary Devices and Style

Shakespeare packs a dense amount of rhetorical flair into these 14 lines.

- Metaphor (Agriculture): The poem is rooted in the earth. Words like rose, riper, bud, spring, and harvest connect human beauty to the natural cycle of crops. If you don't harvest the corn, it rots. The same applies to the Youth.

- Oxymoron: As mentioned, "tender churl" combines gentleness with stinginess. Another subtle one is "niggarding" (hoarding) leading to "waste." Usually, saving prevents waste, but here, saving is waste.

- The Structure: It follows the classic Shakespearean Sonnet form:

- Meter: Iambic Pentameter (da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM).

- Rhyme Scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

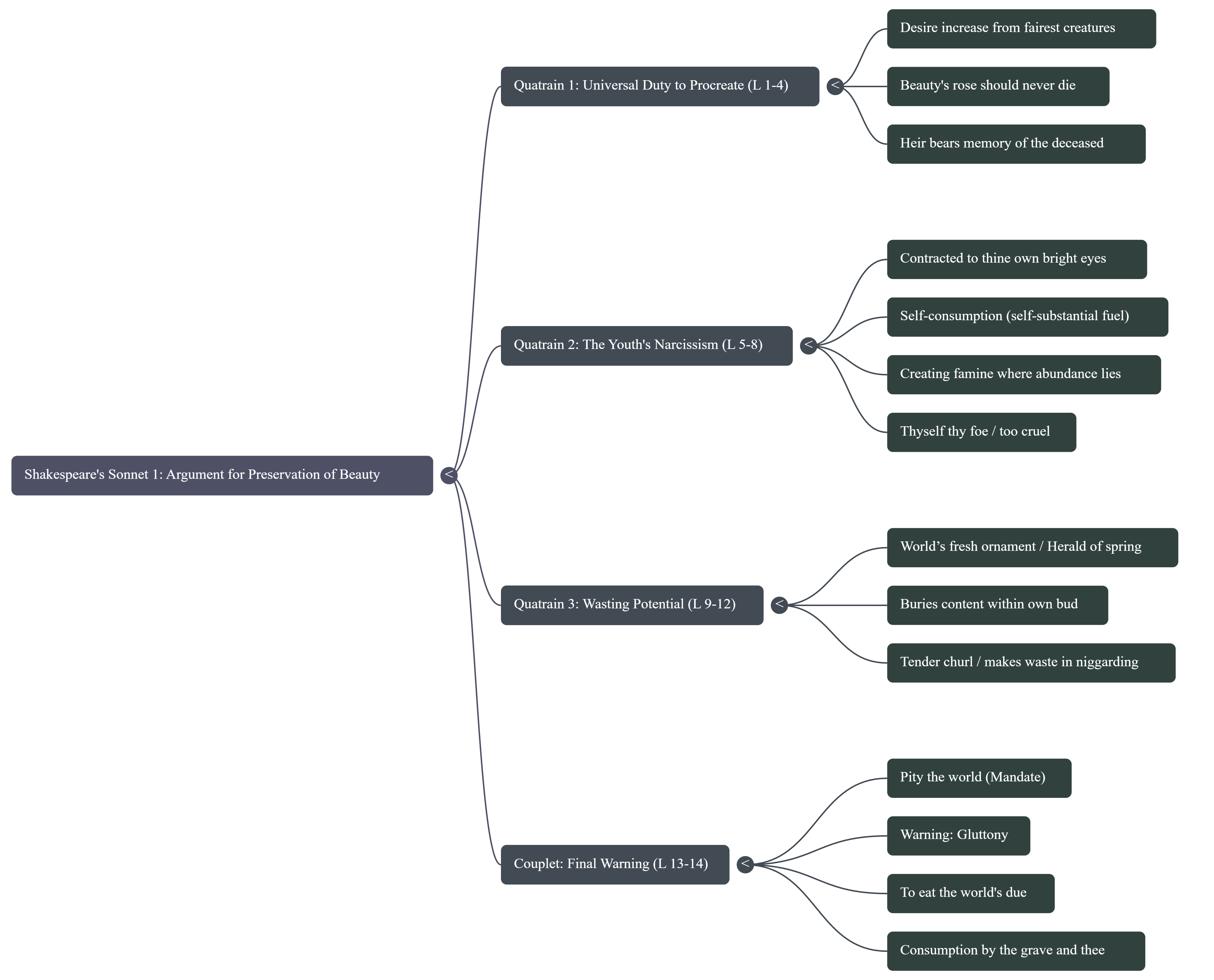

Sonnet 1 William Shakespeare analysis Mind Map

People Also Ask (FAQ)

What is the main message of Sonnet 1? The main message is that beautiful people have a moral obligation to have children. The speaker argues that beauty is a loan from nature, and refusing to reproduce is a selfish act that "wastes" that beauty.

Who is the "Fair Youth" in Sonnet 1? While scholars debate the exact identity, the "Fair Youth" is generally believed to be a young, aristocratic man, possibly Henry Wriothesley (Earl of Southampton) or William Herbert (Earl of Pembroke), who was Shakespeare's patron.

What does "From fairest creatures we desire increase" mean? It means that when we see beautiful living things ("fairest creatures"), we naturally want them to reproduce ("increase") so that their beauty doesn't disappear from the world when they die.

Final Thoughts

Sonnet 1 is a masterful introduction. It establishes the dynamic between the older, wiser Speaker and the young, narcissistic subject. It isn't a love poem in the traditional sense; it’s a lecture on legacy.

By understanding this poem, we unlock the logic of the next 16 sonnets. The Speaker's obsession with the Youth's survival drives the entire narrative. The underlying fear is simple: if you don't leave a mark on the world, did you ever really exist?